The École de Dakar: Crafting National Identity Through Art

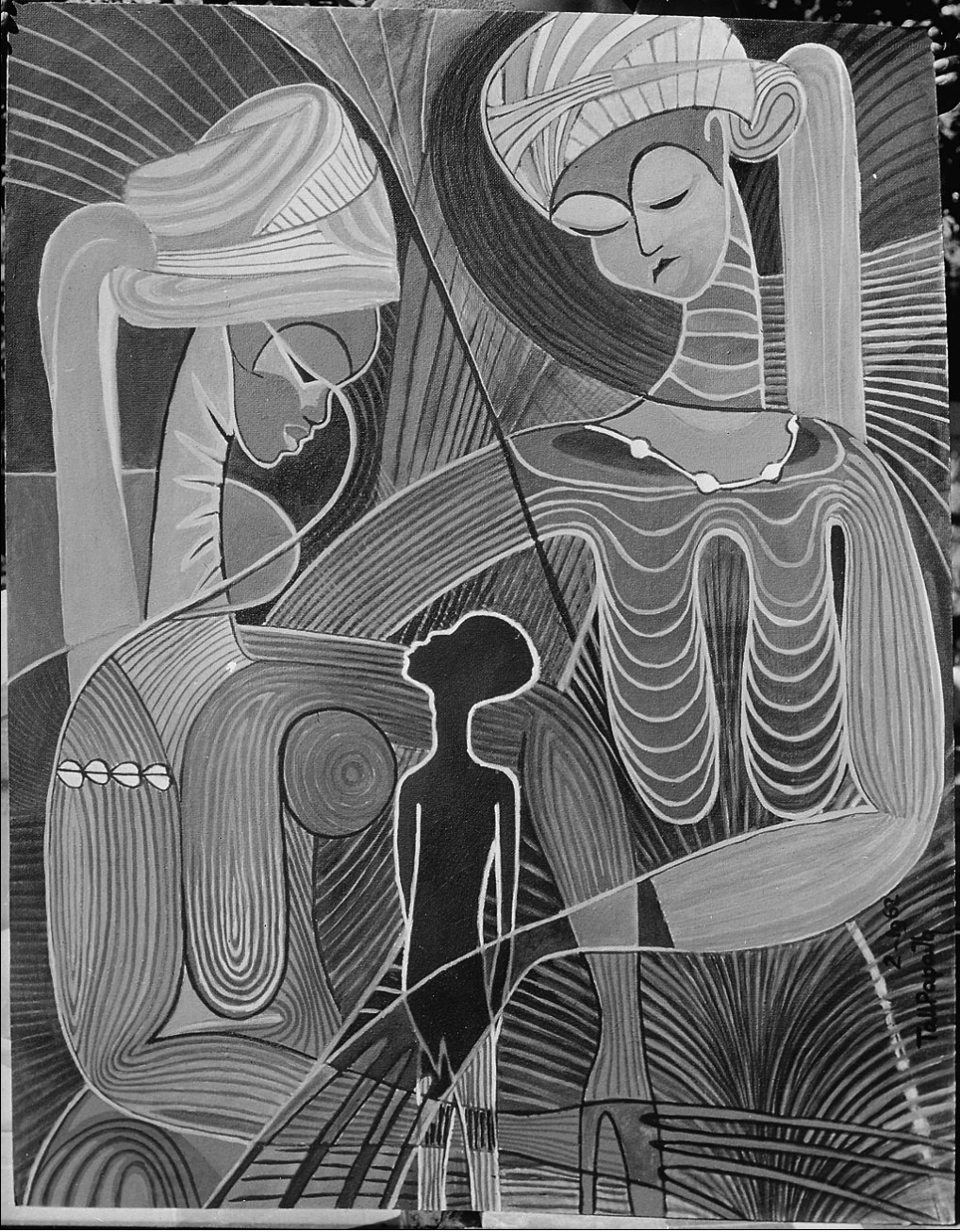

La Chanteuse de Blues (The blues singer), 1984

Iba N'Diaye

French/Senegalese, 1928–2008

source: artnet.com

In the wake of Senegal’s independence in 1960, a powerful cultural movement emerged that would shape not just art, but identity itself. Known as the École de Dakar, or School of Dakar, this group of artists, poets, and intellectuals helped define what postcolonial African modernism could look like—rooted in tradition, yet forward-facing in form and philosophy.

Spearheaded by Senegal’s first president, the poet-philosopher Léopold Sédar Senghor, the movement was deeply tied to the ideals of Negritude. For Senghor, art wasn’t just an aesthetic pursuit—it was a tool of cultural affirmation, pride, and national renewal.

Photograph of President Senghor taken at Musée Dynamique, Dakar, in 1966.

The Vision of Negritude in Visual Form

Negritude, developed by Senghor alongside Aimé Césaire and Léon-Gontran Damas, celebrated the richness of African culture, rhythm, and worldview as an answer to colonial marginalization.

The École de Dakar took that vision off the page and onto the canvas.

Artists were encouraged to explore indigenous forms, symbols, and narratives while embracing technical and formal innovation. The result was a visual language that was uniquely Senegalese but spoke across borders.

Key Artists and Influences

Among the most recognized figures of the École de Dakar were:

Iba N'Diaye — Known for blending Western expressionism with African themes.

Papa Ibra Tall — Fused stylized African iconography with bold, flat color palettes.

Moustapha Dimé — Celebrated for his sculptures exploring ancestral memory.

Mor Faye — Known for experimental forms that pushed the boundaries of abstraction.

Though they worked in different media, what united these artists was their shared commitment to forging an authentic post-independence aesthetic.

The state, under Senghor's leadership, actively supported artists through the Dakar Biennale (Dak'Art), national exhibitions, and art institutions, making Senegal a cultural hub for the continent.

"La Foret aux Souvenirs" (1962)

Papa Ibra Tall

Source: archive.gov

Style and Symbolism

The École de Dakar embraced a range of visual styles, from abstraction to figuration, but consistently drew on:

Indigenous motifs (textiles, masks, griot storytelling)

Spiritual and ancestral themes

Pan-African identity and unity

Modernist experimentation

This synthesis gave rise to a visual vocabulary that felt both timeless and distinctly new.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

The École de Dakar was more than a movement—it was an ethos. It demonstrated how art can shape national consciousness and influence the global perception of African creativity.

Today, the legacy of the École de Dakar lives on in the Dak'Art Biennale, one of Africa's premier art exhibitions, and in the many Senegalese artists continuing to explore questions of heritage, modernity, and cultural memory.

Its influence also echoes in the broader movement of African artists worldwide who are reclaiming narrative authority and aesthetic agency.

Sources: Harney, Elizabeth. In Senghor’s Shadow: Art, Politics, and the Avant-Garde in Senegal, 1960–1995. Duke University Press, 2004.

What It Means to Us

At Infinite Treasures, we view the École de Dakar as a foundational chapter in the story of modern African art. It affirms that African artists are not defined by reaction, but by revelation—boldly crafting beauty that reflects the soul of a people.

Their work reminds us that art is not just seen. It is felt. It is remembered.

And it continues.

““When we reclaim the image of ourselves, we reclaim the power to shape the world.””

Explore the Roots of African Modernism

Read more →

Discover the Legacy in Living Form

Explore artworks inspired by the philosophies of Negritude and the spirit of modern African expression.

View Related Works by Contemporary African Artists →